The limits of hellenization

HOEL

What I want to ascertain is how the Greeks came to know and evaluate these groups of non-Greeks in relation to their own civilisation.

Arnaldo Momigliano

« Ce que je veux établir, c’est comment les Grecs vinrent à connaître et évaluer ces groupes de non-Grecs par rapport à leur propre civilisation. »

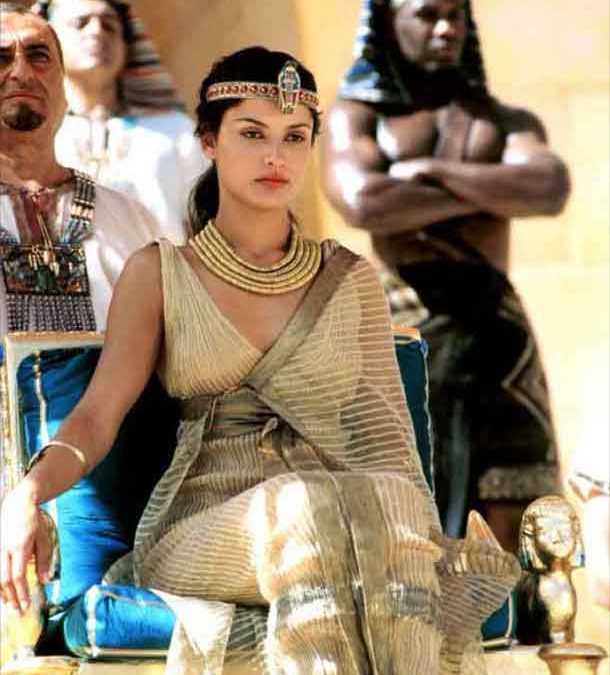

Leonor Varela (Kleopatra - 1999)

The philosophic historian will never stop meditating on the nose of Cleopatra.

… the Hellenistic age saw an intellectual event of the first order: the confrontation of the Greeks with four other civilizations, three of which had been practically unknown to them before, and one of which had been known under very different conditions. It seemed to me that the discovery of Romans, Celts and Jews by the Greeks and their revaluation of Iranian civilization could be isolated as the subject of these Trevelyan lectures. The details are not well known, nor is the general picture clear. There are of course things to be said also about Egypt and Carthage. Hermes Trismegistus emerged from Egypt more or less at the time in which Zoroaster and the Magi became respected figures among the Greeks […]. In both cases the Platonic school played an essential part. Though Plato never made it explicit that Thoth, the inventor of science, was identical with Hermes, the identification is stated by Aristoxenus of Tarentum and Hecataeus of Abdera […]. The search for cultural heroes and religious guides was never confined to one country only. It already embraced Brahmans, Magi, Egyptian priests and Druids by the beginning of the second century B.C, as we know from the authors quoted by Diogenes Laertius in his prooemium. The group went on growing until St Augustine, or rather his source, made it include all the barbarians: ‘Atlantici Libyes, Aegyptii, Indi, Persae, Chaldaei, Scythae, Galli, Hispani’ (Civ. dei 8.9). Two considerations, however, have persuaded me to leave Egypt on the periphery of my enquiry: (1) Egypt had interested the Greeks since Homer as a country difficult to approach and with puzzling customs. It was never treated as a political power. If anything, it was a repository of unusual knowledge. Herodotus gave two ultimately contradictory reasons for spending so much of his time on it, first that ‘the Egyptians in most of their manners and customs exactly reverse the common practice of mankind’ (2.35), and secondly that the Greeks derived so many of their religious and scientific notions from the Egyptians that even those ‘that are called followers of Orpheus and of Bacchus are in truth followers of the Egyptians and of Pythagoras’ (2.81). There was therefore no dramatic change in the Greek evaluation of Egypt during the Hellenistic period, though the rise of Hermes Trismegistus as a god of knowledge was new. (2) Native Egyptian culture declined during the Hellenistic period because it was under the direct control of Greeks and came to represent an inferior stratum of the population. The ‘hermetic character of the language and of the script’, as Claire Preaux called it (Chron. d’Sgypte 35 (1943), 151), made the Egyptian-speaking priest – not to mention the peasant – singularly unable to communicate with the Greeks. The creation of Coptic literature in the new conditions of Christianity indicates the vitality of this underground culture. But the Hellenistic Greeks preferred the fanciful images of an eternal Egypt to the Egyptian thought of their time.

Carthaginian culture, on the other hand, did not decline: it was murdered by the Romans, who, quite symbolically, donated the main library of Carthage to the Numidian Kings (Plin. N.H. 18.22). I would gladly talk about the ideas of the Carthaginians, if we only knew them. Carthage, like the Phoenician cities of Syria, had become increasingly Hellenized. Aristotle had treated Carthage at length as a Greek polis. About 240-230 B.C. Eratosthenes put together Carthaginians, Romans, Persians and Indians as the barbarian nations that came closest to the standards of Greek civilization and specified that Carthaginians and Romans were the best governed (Strabo 1.4.9, P- 66). […]

… about 190-185 B.C. there were many in Greece who looked at Hannibal as a possible saviour from the Romans. […]

During the second century B.C. there must have been a feeling of common danger and interests between Greeks and Carthaginians. It was reinforced by the considerable contribution to Greek philosophy by men of Phoenician stock. Iamblichus gives names of Carthaginian Pythagoreans (Vita Pythagor. 27.128; 36.267). One of the few circumstantial items of information we have suggests that if the Romans had not destroyed Carthage the Carthaginian intellectuals, like the Greek intellectuals, would have become pro-Roman. A young Carthaginian called Hasdrubal came to Athens about 163 and joined the Academy under Carneades three years later. He became famous under the Greek name of Clitomachus and in 127 was recognized as the official head of his school. He dedicated books to L. Censorinus, consul 149, and to the poet Lucilius: he praised or perhaps adulated Scipio Aemilianus about 140. It does not contradict his devotion to the Romans that he should write a consolation for the Carthaginians after the destruction of the city in 146. Cicero still read this work (Tuscul. 3.54); and, being rather thick-skinned in these matters, did not feel the horridness of the situation. One wonders where the Carthaginians were to whom Clitomachus distributed his consolation. He had been caught in the spiral which made his contemporary Polybius the champion of Roman law and order. […]

Unfortunately, there is not enough evidence to make a coherent account of how Carthaginians and Greeks saw each other in the third and second centuries B.C. and how Rome came to profit from the situation – not least by the importation of an African slave who became the most accomplished of the Hellenized dramatists of Latin literature, Terence.

I shall therefore devote the substance of my lecture to a study of the cultural connections between Greeks, Romans, Celts, Jews and Iranians in the Hellenistic period. I shall go back into the classical age of Greece only in so far as it is necessary in order to understand the later times. What I want to ascertain is how the Greeks came to know and evaluate these groups of non-Greeks in relation to their own civilization. I expected to find interdependence, but no uniformity, in the Greek approach to the various nations and in the response of these nations (when recognizable from our evidence) to the Greek approach. What I did not expect to find – and what I did find – was a strong Roman impact on the intellectual relations between Greeks and Jews or Celts or Iranians as soon as Roman power began to be felt outside Italy in the second century B.C. The influence of Rome on the minds of those who came into contact with it was quick and strong.

Hellenistic civilization remained Greek in language, customs and above all in self-consciousness. The tacit assumption in Alexandria and Antioch, just as much as in Athens, was the superiority of Greek language and manners. But in the third and second centuries B.C. trends of thought emerged which reduced the distance between Greeks and non-Greeks. Non-Greeks exploited to an unprecedented extent the opportunity of telling the Greeks in the Greek language something about their own history and religious traditions. That meant that Jews, Romans, Egyptians, Phoenicians, Babylonians and even the Indians (Asoka’s edicts) entered Greek literature with contributions of their own …

Arnaldo Momigliano – Alien Wisdom: The Limits of Hellenization

REVIEW :

~

“During the past 45 years Professor Momigliano (M.) has devoted several books and a vast number of articles — his Contributi now fill seven substantial volumes – to the interpretation of the history of the Jews, Greeks and Romans. The present volume is a further contribution to that central theme. It is, in his own words (p.6), ‘a study of the cultural connections between Greeks, Romans, Celts, Jews, and Iranians in the Hellenistic period’, but the Celts and Iranians are clearly less important. In this field, as in many others, the conquests of Alexander marked a turning point and it was in this period that Greek intellectuals – and the author reminds us that Hellenistic civilisation remained in essence Greek — first became aware of the importance of the Romans, Jews and Celts, and changed their attitude to the Iranians. It should be said that, although M. is particularly concerned with the Hellenistic age, he outlines previous contacts between Greeks and the other civilisations. […] This short book contains a vast amount of information and few scholars could have written it. It is not easy reading, but those who persevere will be in a much better position to appreciate the intellectual side of the Hellenistic age, ‘warts and all’. The author’s aim is ‘to stimulate discussion on an important subject without indulging in speculations.’ I am sure he will achieve it.”

J. R. Hamilton : Prudentia