Athens in the Age of Socrates

HOEL

Among ancient empires bordering the Mediterranean, the Athenian empire was impressive neither for its size nor for its durability. But as the creation of a democratic state it was unique. […]

Over the course of the Athenian experience with empire, the use of writing to hone the skills of debate and to express the principles that made arguments memorable gave rise to new habits of discourse and standards of judgment. These habits in turn provided the foundations of rhetoric, political philosophy, constitutional law, and history. […]

The Athenians were well aware that their city was the home of this literary revolution. Athens was the “school of Hellas,” as Thucydides reports the famous claim of Pericles.

Mark H. Munn

« Parmi les anciens empires riverains de la Méditerranée, l’empire athénien ne fut impressionnant ni par sa taille, ni par sa durée. Mais comme la création d’un Etat démocratique, il fut unique. […]

Au cours de l’expérience athénienne avec l’empire, l’utilisation de l’écriture pour améliorer l’habileté dans les débats et énoncer les principes qui rendirent les arguments mémorables donna naissance à de nouvelles habitudes de discours et normes de jugement. Ces habitudes fournirent à leur tour les fondements de la rhétorique, de la philosophie politique, du droit constitutionnel et de l’histoire. […]

Les Athéniens étaient bien conscients que leur cité était le siège de cette révolution littéraire. Athènes était l’ « l’école de la Grèce », selon la fameuse déclaration de Périclès rapportée par Thucydide. »

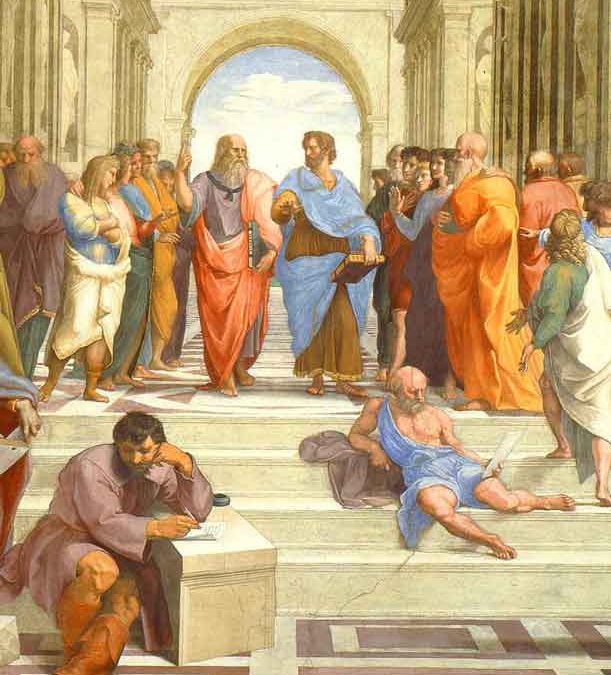

Scuola di Atene (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, 1509–1511)

… Athens, in the final decades of its domination of an Aegean empire, was the central focus of tracts of rhetorical polemic, of reflective drama, of philosophical criticism, and of historical analysis out of which emerged the intellectual tools by which human achievements then and ever afterward have been more keenly judged and compared.

In less than a century (between 478 and 404 b.c.e.) Athens gained and lost an empire. Among ancient empires bordering the Mediterranean, the Athenian empire was impressive neither for its size nor for its durability. But as the creation of a democratic state it was unique. No dynasty or ruling oligarchy controlled the instruments of power at Athens. Political, judicial, and military power were directed by means of public debates in which skilled speakers tried to sway the majority against their rivals’ efforts to do the same. Because power was publicly constructed, contestants for political influence at Athens developed the means to appeal to wide audiences, and to guide popular approval or condemnation not so much according to narrow, sectional interests, but by casting their arguments in terms of transcendent principles. Over the course of the Athenian experience with empire, the use of writing to hone the skills of debate and to express the principles that made arguments memorable gave rise to new habits of discourse and standards of judgment. These habits in turn provided the foundations of rhetoric, political philosophy, constitutional law, and history.

Writing had long been employed among the Greeks, especially as an aide-mémoire for poetry and to give voice to monuments, but in the course of the fifth century it became increasingly the medium for other forms of expression, particularly in prose. Athenian democracy encouraged habits of literacy, both for the creation of public records and memorials and in the personal use of writing as one of the tools to sharpen and amplify rhetoric. The consequences of this trend were various and profound. Poetry at Athens was enriched by the absorption of rhetorical and eulogistic style and content. In this period the public conscience was both entertained and at the same time informed about underlying meanings and ironies within contemporary events through the allegories of tragedy and the farces of comedy, all created and preserved in writing. The enrichment of literary description and rhetorical argument achieved by writers versed in a growing literary heritage enabled critical history to be written, first by Herodotus and then by Thucydides. And many of the same motives that sharpened rhetoric and critical history stimulated the reflective and analytical skills of political philosophy, best known in the person of Socrates and represented in the writings of Plato.

A surprising amount of the foregoing is represented in the literary products specifically of the generation that saw the Athenian empire come to an end, in 404, as the final outcome of the Peloponnesian War. Aristophanes was of that generation, and although Sophocles and Euripides both died in 406 and did not live to see the defeat of Athens by Sparta, they did experience and respond to the convulsions that preceded the final fall. Within that period the Histories of Herodotus were written, and Thucydides, although he was writing after the fall of Athens in 404, began to gather material for his account when the war with Sparta began in 431. Pericles, who died in 429, left no written speeches of his own, nor did any of his contemporaries. But within the following generation, Gorgias, Antiphon, Thrasymachus, and other sophists circulated treatises displaying their rhetorical skills. Increasingly, texts of actual speeches were collected and studied, and by 400 a great number of contemporary speeches were in circulation. Plato was born and educated in these final decades of the fifth century, in the most influential period of his mentor, Socrates. Although Plato’s works belong to the generation after the Peloponnesian War, the event that inspired Plato to write was the trial and execution of Socrates in 399. The same year marked the publication on stone of a substantial body of the laws of Athens. The compilation of these laws, beginning in 411, resulted in the creation of the first known centralized state archive and marked the beginnings of research into constitutional history.

It is not a mere quirk of fortune that such a literate legacy should survive from the last three decades of the fifth century, and not, to any comparable degree, from earlier decades. The habits of reading and the applications of writing burgeoned specifically in the late fifth century, and testimony to the phenomenon is evident in the immediately following generations. Within the fourth century, written works of rhetoric and history, and studies of poetry, laws and institutions, and political philosophy proliferated. All such works referred directly to literary predecessors or implicitly reveal the influence of earlier works. The wide-ranging writings of Aristotle exemplify the tendencies of fourth-century authors to thrive on the works of their predecessors. Yet amidst all this attention to works of the past, as the citations by Aristotle attest, the vast bulk of the literary heritage available to fourth-century authors is traceable to works no earlier than the last third of the fifth century.

The Athenians were well aware that their city was the home of this literary revolution. Athens was the “school of Hellas,” as Thucydides reports the famous claim of Pericles. There is an apparent danger of circularity in accepting this testimony, since Athenian rhetoric naturally praised Athens. But such praise is neither the sole nor even the chief support for this judgment. Much of the political commentary of late-fifth and fourth-century Greece was openly critical of Athenian policies and institutions. Yet it confirms that Athens, in the final decades of its domination of an Aegean empire, was the central focus of tracts of rhetorical polemic, of reflective drama, of philosophical criticism, and of historical analysis out of which emerged the intellectual tools by which human achievements then and ever afterward have been more keenly judged and compared.

What were the conditions that brought standards of criticism and debate to so high a pitch? Part of this inquiry must seek to establish the objects of criticism and debate at Athens, and part must seek to establish when debate at Athens reached such a threshold of intensity that it yielded a lasting record in writing. Put in these terms, an investigation into the conditions that placed Athens at the center of an intellectual and literary revolution must become a historical investigation of the time in which this revolution took place, and particularly of the intersection between political and intellectual culture at that time.

[…]

Our investigation thus comes to focus on the period that Thucydides chose to write about, the Peloponnesian War. It is even possible that our interest in identifying the origins of critical historical analysis has much in common with Thucydides’ motives for writing history. Having lived through this period of ever-intensifying crises, Thucydides was surely responding to the challenge of explaining the destruction of the Athenian empire. But his history never reached that point. Having set out to narrate “the war” that began in 431 and that lasted, as Thucydides notes in 5.26, for twenty-seven years until the surrender of Athens, his work ends abruptly in the midst of its twenty-first year (411/10). Thucydides’ narrative was later continued by others, so we are able to follow the events that Thucydides had in view when he wrote. But the incompleteness of his work is problematic for present purposes, because we lose contact with Thucydides’ intellectual project as it approaches the very time in which it was formed.

Before the abrupt termination of his narrative, Thucydides reveals some of his judgments in view of the outcome of the war. His views are always nuanced, and they likely would have become even more so had he gone on to narrate a further six or seven years of the career of the Athenian empire. But without his judgments on the events accompanying the final defeat of Athens we are hard put to evaluate his meaning in the several passages where he fully contextualizes events but goes on to affirm superlative instances like, “[These were] certainly the best men…who perished in this war,” (3.98.4); “a disaster more complete than any…” (7.29.5); “…a man who, of all the Hellenes in my time, least deserved to come to so miserable an end” (7.86.5); “…the greatest action that we know of in Hellenic history” (7.87.5); and “…a better government than ever before, at least in my time” (8.97.2). We simply do not know how Thucydides would have dealt with the ecstatic highs and bewildering lows that lay in store for the Athenians and their foes in the final six years of the war, or in the civil war at Athens that followed.

Thus as we approach the climax of the story of the greatness of Athens and her fall, we lose the perspective of the man who drew our attention to the subject.

Mark H. Munn – The School of History. Athens in the Age of Socrates